Healing a Fractured World

The Music of Egon Lustgarten (1887 – 1961)

By Alexis Rodda

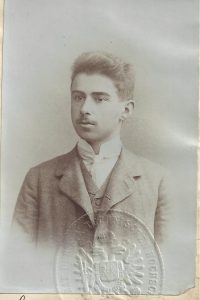

Egon Lustgarten was a composer, music critic, and theorist born in Vienna on August 17, 1887. He matriculated at the k.k. Technische Hochschule Wien in 1905, where he studied Civil Engineering (Bauingenieurwesen) and took classes such as mathematics, Geometry, and technical drawing. His wife, Sophia, recalled that Egon showed an aptitude for many scientific fields, and seemed to have a natural ability for drawing and geography; for example, she observed that he could draw a map from memory after only visiting a location once. However, he also showed great musical aptitude as a child; his wife Sophia writes that it was clear early on in his childhood that he possessed “absolutes Gehör” (perfect pitch), and that the “false tones” from the barrel organ played by the organ grinders on the streets of Vienna were painful to his ears.

Lustgarten as a student, around 1905

Lustgarten as a student, around 1905

His parents had hopes that he would become trained as a technician, or that he would eventually take part in his father’s lumber business. To the chagrin of his parents, he showed little aptitude for the merchant life, and his true passion was music. Indeed, he would often skip his engineering classes in order to study scores with classmate Hugo Kauder in the Imperial Court Library. Recognizing his natural musical talent, and swayed by the fervency of his dedication to music, his parents capitulated.

Lustgarten took two years to train privately before his formal admission to the Vienna Music Academy, studying with Juliusz Wolfsohn and Richard Heuberger. Lustgarten enrolled at the k.k. Akademie für Musik und darstellende Kunst, where he continued to study composition with Richard Heuberger. He also studied conducting with Franz Schalk, a conductor at the Vienna State Opera. Lustgarten earned his certificate of completion from the Vienna Music Academy in 1912.

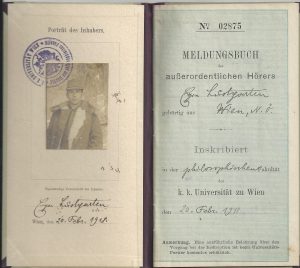

Matriculation paper of Egon Lustgarten at the University in Vienna

Matriculation paper of Egon Lustgarten at the University in Vienna

After serving in the Imperial Army during World War I, he became a Professor of Music Theory and Composition at the Neues Wiener Konservatorium (the New Vienna Conservatory) in 1921. He was remembered in recollections as a trusted teacher and advisor, to whom students came for advice when they found themselves in difficult situations. Lustgarten would sometimes purposely schedule meetings around mealtimes so that he knew his less financially stable students were not lacking in food. His wife recalled that he sometimes encountered difficulties with his colleagues, since he was of a meek nature: “Small in stature and modest in nature, he could never stand up to his colleagues…”

He had a number of prominent students, including Robert Schollum (who managed to build a successful career in Austria after World War II despite his involvement with the Hitler Youth Chorus and National Socialist movement), Kurt Pahlen, and Erwin Leuchter. He was remembered as a well-beloved teacher: Upon the Anschluss in 1938, he and many other professors were dismissed from their positions. One of his students, Roger Derby, an American, demanded a refund for his tuition, saying, “I came to study with Professor Egon Lustgarten, none other.” Viennese music critic Joseph Reitler wrote of Lustgarten, “He may proudly call himself a teacher and leader of a whole generation of composers and pedagogues.”

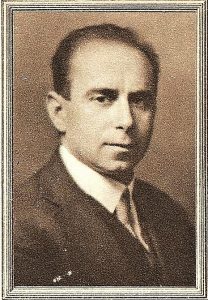

Lustgarten in the early 1930s

Lustgarten in the early 1930s

He was invited to submit the opening essay on Philosophy of Music for the inaugural publication of Die Musikblätter des Anbruch. Der Anbruch was a well-respected musicology publication that was important for the development of new music in Vienna. As more and more composers in the Viennese music scene were forced to emigrate due to the rising political tensions brought on by the repression of the Nazi regime, the publication fell into decline and had its last publication in 1938. From the year of its inaugural publication until Lustgarten’s own forced emigration, Lustgarten was a frequent and highly respected contributor to Der Anbruch and enjoyed success as a prominent music theorist and critic.

He was also a prolific composer. He wrote chamber music, orchestral works, cantatas, choral works, operas, and Lieder. He was a pianist and an active performer and accompanist, but he seemed to have a particular affinity for the voice and opera. His understanding of the voice may have arisen from his role as a collaborative pianist and repetiteur; he even worked with famed Wagnerian soprano Anna Bahr-Mildenburg in her dramatic training school. After emigration, when listing his qualifications and employment preferences, he specifically mentions a desire to work with singers.

In August of 1922 the First International Chamber Music Festival took place in Salzburg. Egon Lustgarten (5th from right) is shown here in the circle of his colleagues (from left): Karl Weigl, Karl Alwin, Wilhelm Grosz, Artur Bliss, Paul Hindemith, Rudi Reti, Ethyl Smith, Paul A. Pisk, Willem Pijper, Egon Lustgarten, Egon Wellesz, Anton von Webern, Karl Horovitz, Hugo Kauder

In August of 1922 the First International Chamber Music Festival took place in Salzburg. Egon Lustgarten (5th from right) is shown here in the circle of his colleagues (from left): Karl Weigl, Karl Alwin, Wilhelm Grosz, Artur Bliss, Paul Hindemith, Rudi Reti, Ethyl Smith, Paul A. Pisk, Willem Pijper, Egon Lustgarten, Egon Wellesz, Anton von Webern, Karl Horovitz, Hugo Kauder

His music was well-received by his colleagues and by critics; a review in the Musikalischer Kurier of Vienna wrote, “In his works are to be found the highest impulsivity and abundance of fancy, restrained by an extraordinary power of concentration, a most determined sense for construction, and a superior government over all technical matters.” One of his most significant compositions was his opera, Dante im Exil, completed in 1938 and meant to have its premiere that year at the Viennese State Opera. After studying the score of Dante, well-known conductor Joseph Krips proclaimed Lustgarten’s opera “the best opera of the 20th century.” Due to the Anschluss of Austria by Nazi Germany in 1938, Dante im Exil would never see its premiere at the Staatsoper.

Lustgarten was born into a Jewish family, but officially submitted his withdrawal from the Jewish community in 1925. Eleanor Paul, Lustgarten’s daughter, writes this of her father’s connection to his faith: ““He was born into a Jewish family, but early in his life found his way to Anthroposophy, the spiritual teachings of Dr. Rudolf Steiner, and with it, his way to Christianity.”

However, the Nuremberg Race Laws passed in 1935 by Nazi Germany defined a Jew as: “One who is descended from two Jewish parents,” and when Austria was annexed by Nazi Germany on March 12, 1938, the escalation of violence against Jews in the forms of intimidation, humiliation, and terrorization was swift. The definition of “Jew” was officially adopted into Austria on May 20, 1938. By this definition, Egon Lustgarten was racially classified as a Jew in Nazi Germany, a categorization which would later come to define the rest of his life.

Due to the rising pressure against Jews in Austria under the Third Reich, Lustgarten, along with his wife Sophie, and daughter, Eleanor, left Austria on August 22, 1938 and emigrated to the United States. His emigration marked the end of any kind of real career success, as he found recognition neither as a composer nor a music scholar after his arrival in the United States.

Sophia Elisabeth and Egon Lustgarten in the 1950s on Long Island

Though Lustgarten continued to compose after his emigration—he even staged a small semiprofessional production of his opera The Blue Mountain in 1945—financial difficulties plagued him for the rest of his life, and few seemed interested in his compositions. His music was strongly influenced by late Romantic composers like Brahms, Wagner, and Schubert, and over the course of the war and postwar years, his music had fallen out of style. His compositional voice did not resemble the modernism of Schoenberg, nor did it share the sweeping quality of Korngold’s grand Hollywood scores. Lustgarten continued to compose prolifically after his emigration and attempted to promote his works for possible performance or study even to the end of his life. He returned to Europe towards the end of his life to make one last effort towards having his music explored more seriously by musicians and conductors in Europe, but Lustgarten, a product of late Romanticism, found no success in the new and unfamiliar musical landscape. Despite Lustgarten’s resilience and perseverance, his music lies in obscurity, first in Munich, Germany, after his late daughter Eleanor G. Paul bequeathed the materials to the Lahr von Leïtis Archive; the Archive is now housed in Vienna at the Exil.arte Zentrum. Throughout her lifetime, Eleanor Paul tried to promote her father’s music, strong in the belief that his music was worthy of becoming a more prominent fixture in both Austrian and American musical history.

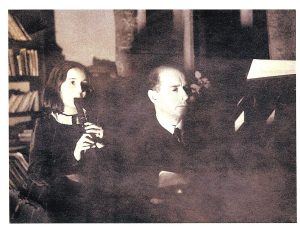

Egon Lustgarten, making music with his daughter Eleanor Paul

Egon Lustgarten, making music with his daughter Eleanor Paul

Lustgarten’s music is something of an enigma. He experimented with many different musical styles; his skill in these various styles goes back to his “determined sense for construction.” He had such a skill in the actual art of composition, that he sometimes was seen as lacking a unique compositional voice. One critic said of his early works “However sincere, they lacked forceful traits or striking originality.”

With a retrospective view, we can see Lustgarten’s music as not necessarily lacking originality, but perhaps not considered experimental enough in the context of the modernist music movement pioneered by Arnold Schoenberg. His early works are firmly late Romantic; Liebliche Harfe Lasset Erklingen is a beautiful example of the Romantic compositional style. He became his most experimental midway through his career, in the 1920’s; Japanisches Liebeslied and the song cycle Nachtgesichte illustrate the extent of his experimentation. With Dante im Exil, he strikes a balance between modernism and romanticism. The vocal parts, while tonal, weave disparate fragments of thematic materials to create inventive melodic lines. Lustgarten also seemed to be imagining the potential of the modern orchestra when he wrote the piano reduction of Dante.

After his emigration, his compositional style shifted. The Blue Mountain is an excellent example of his post-emigration style; in general, the vocal line tends to be more simplistic, though the melody still wanders into tonally ambiguous territory. The piano part has the burden of musical complexity in contrast with the simpler vocal lines. A virtuosic pianist, like Lustgarten himself, is needed to interpret the piano score, which seems to have been written with an orchestral rendering in mind.

Egon Lustgarten shortly after his arrival in the U.S.

Egon Lustgarten shortly after his arrival in the U.S.

Lustgarten’s music has been lost to history entirely by chance: he was an integral member of the Viennese classical music scene before the Nazis interrupted his potentially fruitful career with their policies of racism and violence. Lustgarten displayed incredible resilience and perseverance even in the face of unimaginable challenges, but his music was never given the chance to make its mark in history due to circumstances beyond his control. It is important to set the precedent of reversing the erasure of composers and artists such as Lustgarten, especially since we are seeing similar types of suppression today. We need to be aware of what we lose when we allow the artistic canon to be controlled by hate and racism. His music is deserving of a place in late Romantic and early modernist music history.